Lecture 17

Quicksort

MCS 275 Spring 2022

Emily Dumas

Lecture 17: Quicksort

Course bulletins:

- Project 2 due 6pm Fri 25 Feb.

- Project 2 autograder opens Mon 21 Feb.

- Homework 6 posted. (Shorter than usual.)

Transformation vs mutation

Last time we wrote a mergesort function that acts as a transformation: A list is given as input, a new sorted list is returned.

Another approach we could consider is sorting as a mutation: A list is provided, the function reorders its items and returns nothing.

In place

A sorting transformation always uses an amount of memory that is at least as large as the list. (It needs a second list to store the output, after all.)

A sort that operates as a mutation has the possibility of using only a fixed amount of memory to do its work.

Doing so is called an in place sorting method.

Quicksort

A recursive in place sorting method that, like mergesort, is reasonably efficient and widely used.

Partition

Let's first study something weaker than sorting.

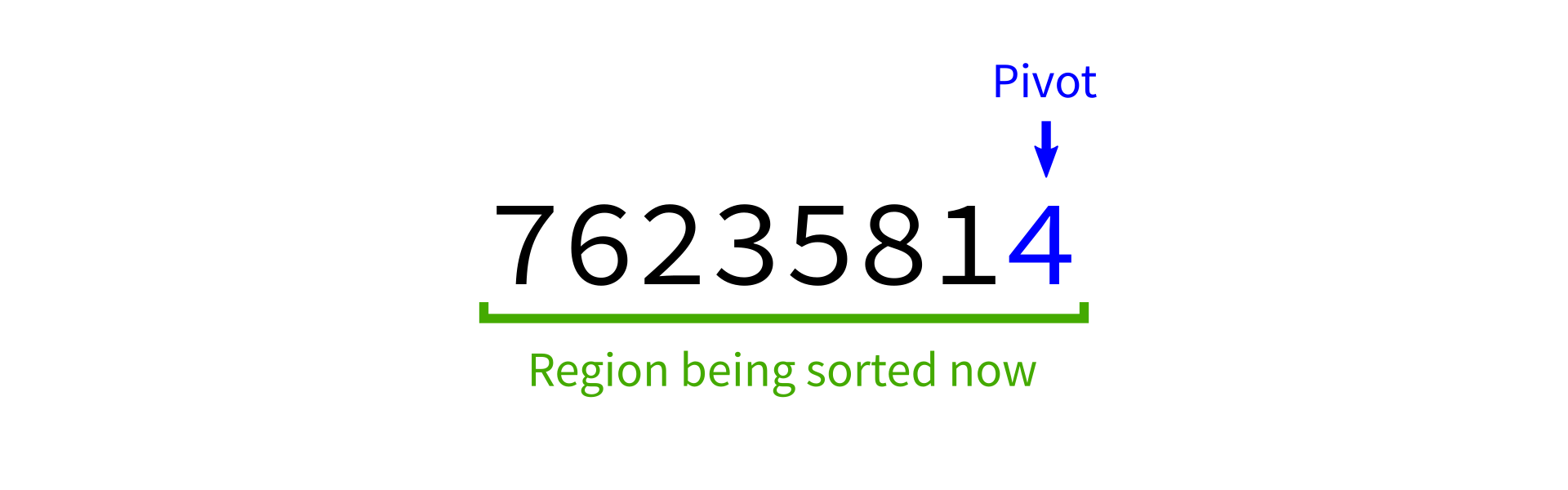

Given a list L, let p be the last element of L.

We want to rearrange L so that it looks like:

[ items < p, p, items ≥ p ]

We say L has been partitioned at p, and we call p the pivot.

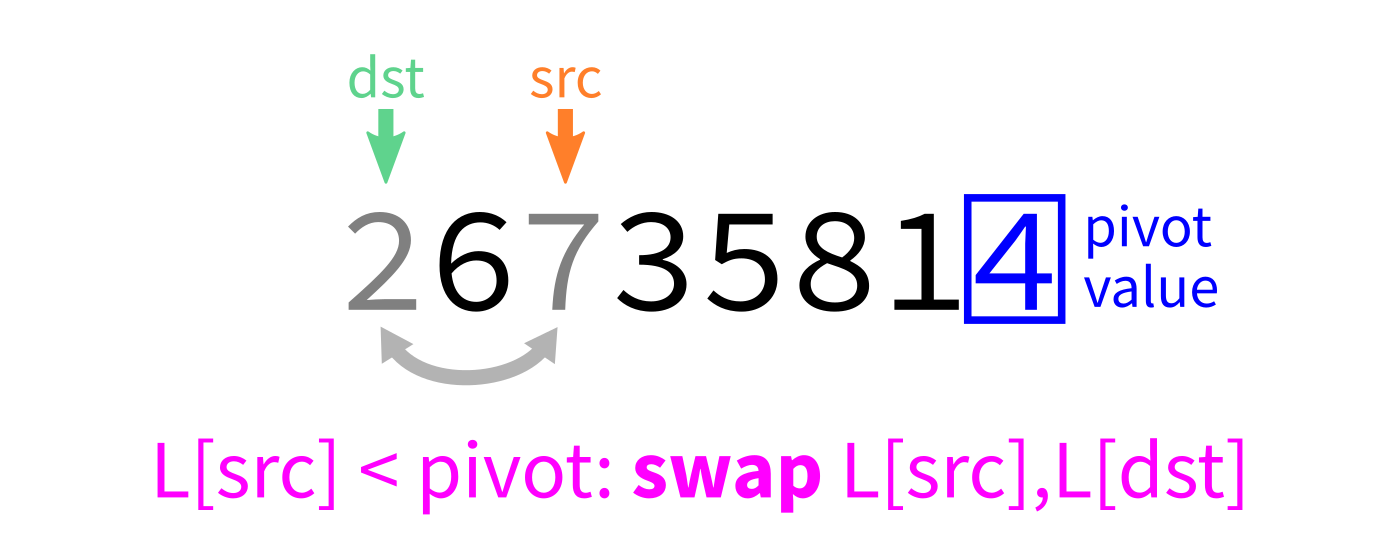

Partition algorithm

Idea: Move all small things to the front.

After partition

The two chunks of the list on either side of the pivot may not be sorted.

But we could bring each of them closer to being sorted by partitioning them...

Quicksort summary

Starting with an unsorted list:

- If the list has 0 or 1 elements, return immediately.

- Otherwise, partition the list.

- Quicksort the part of the list before the pivot.

- Quicksort the part of the list after the pivot.

It's divide and conquer, but with no merge step. The hard work is instead in partitioning.

Quicksort visualization

Coding time

Let's implement quicksort in Python.

quicksort:

Input: list L and indices start and end.

Goal: reorder elements of L so that L[start:end] is sorted.

- If

(end-start)is less than or equal to 1, return immediately. - Otherwise, call

partition(L)to partition the list, lettingmbe the final location of the pivot. - Call

quicksort(L,start,m)andquicksort(L,m+1,end)to sort the parts of the list on either side of the pivot.

Why discuss algorithms?

Python lists have built-in .sort() method. Why talk about sorting?

- Study cases of easy-to-explain problems solved in clever ways.

- See patterns of thinking that work in other settings.

Evaluating sorts

Last time we discussed and implemented mergesort, developed by von Neumann (1945) and Goldstine (1947).

Today we discussed quicksort, first described by Hoare (1959) and the simpler partitioning scheme introduced by Lomuto.

But are these actually good ways to sort a list?

Efficiency

Theorem: If you measure the time cost of mergesort in any of these terms

- Number of comparisons made

- Number of assignments (e.g.

L[i] = xcounts as 1) - Number of Python statements executed

then the cost to sort a list of length $n$ is less than $C n \log(n)$, for some constant $C$ that only depends on which expense measure you chose.

Asymptotically optimal

$C n \log(n)$ is pretty efficient for an operation that needs to look at all $n$ elements. It's not linear in $n$, but it only grows a little faster than linear functions.

Furthermore, $C n \log(n)$ is the best possible time for comparison sort of $n$ elements (though different methods might have better $C$).

Quicksort

Is quicksort similarly efficient?

References

- Making nice visualizations of sorting algorithms is a cottage industry in CS education. Some you might like to check out:

- 2D visualization through color sorting by Linus Lee

- Animated bar graph visualization of many sorting algorithms by Alex Macy

- Slanted line animated visualizations of mergesort and quicksort by Mike Bostock

Revision history

- 2022-02-18 Initial publication