MCS 275 Spring 2024 Worksheet 2¶

- Course instructor: Emily Dumas

Topics¶

This worksheet corresponds to material from lectures 1-3, which contained the Python tour and a bit of object-oriented programming. Thus it contains:

- General Python review exercises at MCS 260 level (but a bit more challenging than worksheet 1)

- Practice with classes, instances, and methods

Instructions¶

- This isn't collected or graded. Work on it during your lab on Jan 16 or 18.

- This worksheet prepares you for Homework 2. (Worksheet

nalways prepares for Homeworkn) - These instructions will be essentially the same for every worksheet, so we'll stop writing them out explicitly. (Homework will always have full, detailed instructions.)

Resources¶

These things might be helpful while working on the problems. Remember that for worksheets, we don't strictly limit what resources you can consult, so these are only suggestions.

- Lecture 1

- Lecture 2

- Lecture 3

- MCS 275 Python Tour

- MCS 275 sample code repository

- Downey's book, Think Python

- MCS 260 course materials from Fall 2021:

1. Increasing run length¶

Suppose you have a list of integers. Even if the list is not entirely in increasing order, there are sometimes parts of the list that are in increasing order.

For example, consider L = [1,21,4,17,38,39,35,22,0,6,2,5]*. The list is not in increasing order, but the first two elements (i.e. L[0:2] or [1,21]) are in increasing order. Also, if you take the slice L[2:6], which is [4,17,38,39], that is in increasing order.

Let's call a slice of a list that is in increasing order an increasing run. A given list of integers can have many increasing runs.

In the example given above, the longest increasing run you can find in L is L[2:6], and it has length 4.

Write a function IRL(L) that takes a list L and returns the length of the longest increasing run within L. In order for that to make sense, you should assume the elements of L can be compared to one another using > and < and ==, but it shouldn't matter exactly what their types are. If it helps in thinking about the problem, you could imagine they are integers.

Special cases (not necessarily requiring special handling, but explained here to clarify the extremes):

- If

Lis empty, the function should return 0 - If

Lis in decreasing order, the function should return 1 because a slice with one element can be considered to be in "increasing order", and that would be the longest increasing run.

* The sample list L shown above had a typo which was corrected on Jan 16.

Here are some sample outputs:

IRL([40, 1, 63, 20, 53, 9]) # [1,63] and [20,53] are the longest, each has length 2

IRL([22, 40, 47, 46, 26, 45, 25, 30, 47, 40]) # [22,40,47] and [25, 30, 47] are the longest

IRL([78, 26, 1, 20, 72, 19, 44, 50, 59, 67]) # [19, 44, 50, 59, 67] is the longest

IRL([1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]) # The entire list, of length 8, is increasing!

IRL([]) # no elements = no increasing runs = max increasing run length 0

IRL([275]) # [275] is the longest increasing run

IRL([10,8,6,4,2]) # [10] and [8] and [6] and [4] and [2] are the longest, each has length 1

Hint: Here is one possible strategy: Use a for loop to scan through the list, keeping track of the current element and the previous one. As you go, make note of how many successive elements have been increasing. Use another variable to hold the largest number of increasing elements seen so far, and update it as needed on each iteration.

2. Zitterbewegung¶

Zitterbewegung is a German word meaning "jittery motion".

This is an exercise in object-oriented programming.

Make a class ZBPoint that stores a point (x,y) in the plane with integer coordinates.

The constructor should take (x,y) as arguments and store them as attributes.

Add a __str__ method Printing an instance of this class should produce a nice string like

ZBPoint(17,-2)Also include a method .jitter() that will move the point up, down, left or right by one unit. It should be a mutation (modifying the coordinates, not returning anything). The direction should be chosen at random (e.g. using random.choice or random.randint from the Python random module that you can import with import random.)

The code below demonstrates how you would use this class to create a point at (20,22) and then let it jitter about for 30 steps, printing the location each time.

P = ZBPoint(20,22)

for _ in range(30):

print(P)

P.jitter()

3. Text circles¶

In this problem it's important to use a big terminal window, at least 80 characters wide and 40 lines tall.

Write a program circle.py that takes one command line argument, r, and then prints 40 lines of text, each containing 80 characters. The output should make a picture of a circle, using characters as pixels that can be either "on" (@ character) or "off" (` character). Whenr=20the circle should be slightly too big to fit in the block of text, and whenr=1` it should be nearly too small to have any empty space inside.

For example, here is possible output for r=5.

And here is possible output for r=15:

This exercise is deliberately a little vague about how to go about this, but here is a hint: Each character you print corresponds to a certain point (x,y) in the plane, with character 40 on line 20 corresponding to (20,20). The factor of 2 in the y coordinate is because haracters in a terminal are usually twice as tall as they are wide. Calculating the coordinates of the next character to be printed inside of the main loop will be useful. Then, how would you decide whether to print a " " or a "@"?

4. Recurrence time histogram¶

This builds on the ZBPoint class from problem 2.

Suppose you start a ZBPoint at (0,0) and then repeatedly call the method .jitter() until the first time it returns to (0,0). The number of steps it takes to do this is called the recurrence time. It's possible that this may never happen, but that is very unlikely. (It can be shown that the probability it will eventually return to (0,0) is 100%.)

Write a program that runs this process 1000 times and records the recurrence times. (It's OK to give up on a point if it's taken 200 steps and hasn't yet returned to (0,0).) The program should then print a table showing how many times each recurrence time was seen (a histogram). Here's an example of what it might look like:

Ran 1000 random walks starting at (0,0). Of these:

235 returned to (0,0) after 2 steps

76 returned to (0,0) after 4 steps

51 returned to (0,0) after 6 steps

31 returned to (0,0) after 8 steps

24 returned to (0,0) after 10 steps

17 returned to (0,0) after 12 steps

18 returned to (0,0) after 14 steps

7 returned to (0,0) after 16 steps

6 returned to (0,0) after 18 steps

13 returned to (0,0) after 20 steps

7 returned to (0,0) after 22 steps

8 returned to (0,0) after 24 steps

9 returned to (0,0) after 26 steps

4 returned to (0,0) after 28 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 30 steps

5 returned to (0,0) after 32 steps

3 returned to (0,0) after 34 steps

5 returned to (0,0) after 36 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 38 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 40 steps

3 returned to (0,0) after 42 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 44 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 46 steps

4 returned to (0,0) after 48 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 50 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 52 steps

7 returned to (0,0) after 54 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 58 steps

3 returned to (0,0) after 60 steps

4 returned to (0,0) after 62 steps

4 returned to (0,0) after 64 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 66 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 68 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 70 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 72 steps

3 returned to (0,0) after 76 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 78 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 80 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 82 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 84 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 86 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 92 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 94 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 96 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 98 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 106 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 108 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 110 steps

4 returned to (0,0) after 116 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 118 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 122 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 124 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 126 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 128 steps

3 returned to (0,0) after 130 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 134 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 136 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 138 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 142 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 144 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 146 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 156 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 158 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 160 steps

3 returned to (0,0) after 162 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 166 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 174 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 178 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 180 steps

3 returned to (0,0) after 184 steps

1 returned to (0,0) after 190 steps

2 returned to (0,0) after 198 steps

376 didn't return to (0,0) after 200 stepsExtra challenges¶

I recommend you don't work on these unless you finish the other problems and have extra time in lab or want an additional challenge on your own time.

A. Efficiency of IRL¶

This doesn't have a solution per se, but it asks you to evaluate and possibly improve your solution to problem 1.

There are lots of ways to solve problem 1, and some are more efficient than others. That is, if L is very long, there are some approaches where IRL(L) will return quickly, while a valid but different way of writing the function would take a very long time to return an answer.

Try your IRL function on a list of 10,000 or 100,000 integers in some sort of random order. An efficient solution should handle this very quickly (less than a second). If yours takes much longer, can you think of ways to make it faster (but still correct)?

The code below could be used for the necessary testing, if you add it to a file that contains your IRL function.

import random

import time

test_length = 100_000

test_input = list(range(test_length))

random.shuffle(test_input)

t0 = time.time()

k = IRL(test_input)

delta_t = time.time() - t0

print("IRL for a list of {} random integers returned {} after {:.2f} seconds".format(

test_length,

k,

delta_t

))

B. Prettier circles¶

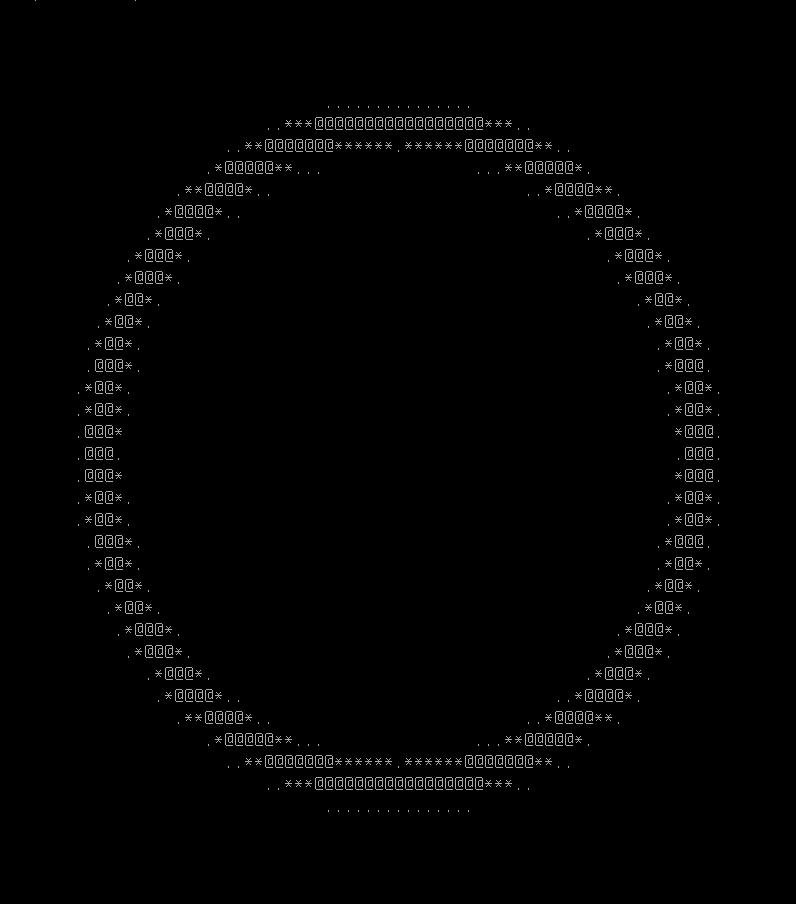

Make a program circle2.py so that it makes circles with softer edges, like this:

Revision history¶

- 2024-01-15 Initial release

- 2024-01-16 Important typo fixed: sample list

Lin problem 1 was missing element38